In a world where the cachet of "alternative" is largely reserved for the left, Pat Buchanan's boat rocking dissents are a welcome challenge to conventional wisdom from the right.

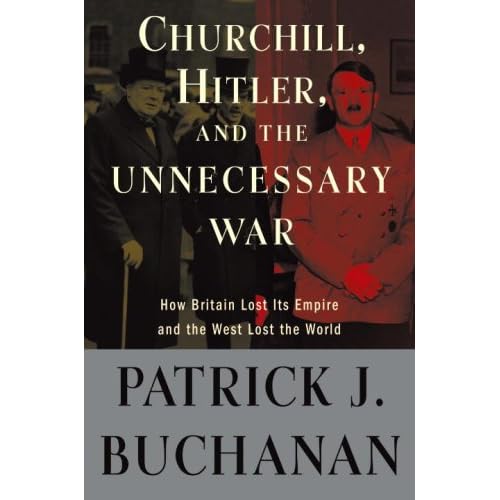

In a world where the cachet of "alternative" is largely reserved for the left, Pat Buchanan's boat rocking dissents are a welcome challenge to conventional wisdom from the right.I'll confess that I haven't read Churchill, Hitler, and "The Unnecessary War": How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World. However, the appearance of this book should not be the least bit surprising to followers of Buchanan's thinking in recent years and his description of the world wars as a "Civil War of the West". Paleo-conservatism is not politically viable today next to the alternatives of left-liberalism and neo-conservatism and that is largely because elements of paleo-conservatism reject the universalization of identity in favour of a particularistic "blood and the soil" narrative and that sort of thinking is seen in many corners as the intellectual root to the horrific excesses of Nazism. Buchanan's anxiety over immigration was the accepted wisdom prior to World War II, yet after it became a political third rail. It's only natural that Buchanan is going to lament the event that empowered cultural relativism and pushed his identity politics to the fringe.

Christopher Hitchens' critique of the book, and his conclusion that it not only "stinks" but has "sinister" elements, is likely to be one of the most popular critiques. Whether it is truly a book review is an open question. Hitchens doesn't seem to object to the Buchanan's scholarship so much as to Buchanan's weltanschauung: e.g. "[a]s the book develops, Buchanan begins to unmask his true colors more and more." In many respects, this proves the point about paleo-conservatism's marginalization: one doesn't argue with it, it's assumptions are rather self-evidently evil such that one need only expose it.

Hitchens takes strong exception to Buchanan's contention that, as Hitchens puts it, "the Nazi decision to embark on a Holocaust of European Jewry was 'not a cause of the war but an awful consequence of the war.'" According to Hitchens, "This absolutely will not do." On this point, Hitchens' absolutism is quite out of place. Why? Because the greatest evil of war is the breakdown in the norms of human behaviour that come with it. The Anglo-French guarantee of the Polish corridor transformed a tragedy for Poland into a tragedy for all of Europe. Now, perhaps it was a necessary tragedy. But that's an intricate hypothetical involving an enormous amount of abstraction about the "greater good" when the practical consequence of western efforts to weaken Hitler's hand would merely be to strengthen Stalin's unless the west could project its own power into the area (eastern Europe) in such a way as to keep Stalin from filling the vacuum (as an aside, this is why I am more dubious about military intervention in Iraq or Afghanistan than in Georgia or North Korea: in the former cases you have Iran or some unsavoury local warlord ready to fill the power vacuum, in the latter you've got the relatively respectable governments in Tbilisi and Seoul). Indeed, Buchanan's central contribution here is his review of the particular facts that illustrate how the non-self-interested "what brings a greater good for eastern Europeans" argument was not only dubious but was not even a significant consideration at the time. The historical evidence indicates that Hitler was interested in a war with the East, not the West. Atrocities are committed during times of war that are not committed to anything approaching the same extent when the legitimacy or reach of state authority is not under such direct and significant challenge. The scale of the crimes of peacetime Nazi Germany and wartime Nazi Germany are not comparable. Hitchens contends that it is "fatuous" to suppose that, without the "occasion" of the Second World War, "the Nazis would not have found another" occasion for "the organized deportation and slaughter of the Jews."

It is, in fact, quite the opposite of "fatuous". It is a question at the heart of a humanitarian, as opposed to ideological and impractical, anti-war policy. If one were to say, "it is outrageous to suggest that Germany's claim to the Polish corridor was so strong that Germany was justified starting World War II", one would be missing the point entirely. The point is that it is less than absolutely obvious that Germany's claim was so weak that expanding a German-Polish war into a war with the west would ultimately generate fewer horrors on net when a hulking Soviet Russia was right in the thick of it as well. Keep in mind here that eastern Europe was largely liberated from Moscow's communist authoritarianism in 1989 without the west firing a shot. The extent to which emancipatory effects actually follow from escalations of violence as opposed to heightened horrors is thus not a "fatuous" question.

Central to Hitchens thesis is the unelaborated assumption that the west was not facing a highly contentious "lesser of two evils" scenario with respect to Hitler vs Stalin. As a former Trotskyite, it is not surprising where Hitchens' sympathies lie. According to Hitchens, in the wake of 1945, "all the way from Portugal to the Urals, the principle of human rights" are the norm. "Human rights" were the "norm" "all the way ... to the Urals" in 1950? Hitchens doesn't say 1950, of course, he says, "today", but that makes the enormous assumption that whereas Soviet authoritarianism eroded over time, Nazi authoritarianism would not have. Look at the mentality of Germans today, and it is clear that the Germans are no more inherently racist, warmongering, authoritarian, or brutal than the Russians. The looting and expulsions that went on behind Russian lines in Georgia in 2008 have enough parallels to 1945 that it is, in fact, plausible to argue that the Russian mentality is more consistently resistent to western values than the German.

Unfortunately for my view of Buchanan, he undermines much of his own argument about how Churchill unwisely fueled the spiral of violence when Buchanan says, in reference to the contemporary conflict in Georgia, that "Georgia started this fight – Russia finished it. People who start wars don't get to decide how and when they end." Even if it is true that Georgia "started this fight", one could turn that around to say that since Germany started the fight in September 1939, any and all horrors subsequent, such as the Red Army's raping of literally millions of German women in 1945, should somehow be excused.

If humanity is going to step out of the shadow of hatred, we have to stop tying one instance of injustice to another and instead stand up and put a stop to the spiral. That doesn't mean arbitrarily choosing a point and saying, "no more from here", since that might just enshrine the outcome of the latest injustice. It means actually weighing the proportionality of each response and considering the particular messy details of the conflict.

Buchanan's column on Georgia isn't paleo-conservative, in my view, since it is chock full of the same supposed equivalencies trotted out by the left: Israel, Kosovo, etc etc. Paleo-conservatism, at its core, is particularistic, by which I mean it rejects the applicability of generalized abstractions, in particular the universal brotherhood of man. The fact I'm a male of northern European heritage, for example, says a great deal about me, and it isn't a moral statement but rather an insight. It's an explanation for why I think what I think and do what I do, not a justification. Buchanan gets away from this thesis when he assumes the relevance of a string of conflicts involving different cultures and conditions instead of considering what is unique to each particular case.

2 comments:

What do you think about the creeping nationalization of the FIRE sector in the U.S.?

Sorry for not replying earlier, but with respect to your question, that's a column in itself.

Briefly, though, it is special case because it is not motivated by any appreciation for nationalization so much as an appreciation of the fact that if the state doesn't save a card in the house of cards from collapsing, the whole house will come down.

They would've let Lehman go down, I think, but AIG was just too big. If AIG went bankrupt, everyone AIG owed would in turn be threatened with bankruptcy. If AIG's business model was obsolete, then sooner or later it has to die. But if it just has a liquidity crisis, recapitalizing it does not necessarily herald a new area of government control of how capital is allocated and goods and services produced.

Post a Comment