For my undergraduate degree I majored in philosophy, and one of the ideas I picked up then that has stuck with me is that the "coherence" theory of truth has a lot to recommend it. It answers many of the various objections that epistemological skeptics make and that subjectivists make to objectivists while retaining the primacy of logic and rejecting the metaphysical premises behind moral relativism. To oversimplify, you might not agree with someone else's world view, but you still have to keep your own world view coherent, and once it is established that both you and another person both believe in certain basic principles, if you disagree on some derivative matter one of the two of you is more wrong than the other.

I write this as a preamble to making three comments about the U.S. economic and political debates. Allow me to take as the first example what PolitiFact called the "Lie of the Year": the Romney campaign's Jeeps and China ad.

How effective a criticism of PolitiFact's decision is it to note that every word of the ad is actually true? Presumably not very, since that's held to not be the issue. At the time, Politifact said, "In this fact check, we examine whether the sale of Chrysler came at the cost of American jobs" instead of examining what the ad actually claimed. According to PolitiFact, the ad "presents the manufacture of Jeeps in China as a threat, rather than an opportunity to sell cars made in China to Chinese consumers." Now that IS true, it is presented as a threat on the basis of the well established economic principle of opportunity cost (corporate resources spent on expanding plant in China are resources not spent on expanding plant in the U.S.) but the question is why outsourcing suddenly became an "opportunity" when Politifact treaded lightly on the Obama campaign's many charges that Romney was running to become Outsourcer in Chief. Where is the coherency? Now it's true that Romney could be challenged on his own "coherency" in choosing this line of attack by noting his track record at Bain. But that's actually a charge of hypocrisy, not a truth claim. As Ryan Chittum at the Columbia Journalism Review put it:

Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post dodged the fact that what the ad said was true by declaring that "The series of statements in the ad individually may be technically correct, but the overall message of the ad is clearly misleading." Kessler assigned his most damning designation of Four Pinnochios on this basis, yet he assigned zero to Obama's claim in his second debate with Romney about his communications regarding Benghazi which were only technically correct and technically was not even technically correct. The Columbia Journalism Review was founded by Victor Navasky, who has used his publication The Nation to, amongst other things, argue that Alger Hiss wasn't a spy for Stalin despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The CJR's Chittum nonetheless points out a mitigating factor re the Jeeps and China ad, namely that it started with a Bloomberg story with problematic wording and then was amplified inaccurately by a Washington Examiner blogger (before actually being dialed back in the Romney ad transcript from what the Examiner said). No such mitigating factor exists with respect to Obama's misleading claim in the second debate. Instead of getting "caught up in the liberal echo chamber," Obama's decision to create the impression that he called Benghazi a terrorist attack from Day 1 was a decision to create something, not picking up to forward on a liberal attack line already in circulation. Politfact, of course, also took a pass when it came to rating Obama's remarks, instead seeing the back and forth with Romney at the second debate as an opportunity to mark down Romney, calling his criticism of Obama on the point "half true." The bottom line here is that it's a mug's game to try and expose "fact checking" bias by pleading the "facts." One has to make an appeal to coherency, not correspondence.

The moral status of abortion may be an example of an issue whereby the level at which disagreement begins is too fundamental for either side to prove the either side to be definitively wrong. There just aren't many commonly held premises, even when drilling down to the metaphysical level. One ends up appealing to a "correspondent" theory of truth, i.e. arguing that the other side's beliefs do not correspond to reality. If one person's view of reality happens to be entirely materialist (that nothing, not even consciousness, exists apart from matter and energy) while the other is metaphysical dualist, the disagreement will be pretty fundamental.

But most debates between "subjectivists" and "objectivists" are over matters of degree within a coherence construct. If the coherence test is applied to such an extent that the "edge" of its applicability circumscribes all of human consciousness, and that metaphysical premise itself forms a common cornerstone, then notions of "subjectivity" drop out as irrelevant, à la Wittgenstein's beetle in a box. There might be another universe out there, but we are living in this one.

[The ad is] saying that Chrysler’s Italian owners “are going to build Jeeps in China.” But happens to be true, even if it was happening before 2009 under its German and private-equity ownership. Cars made overseas by an American company (even one with Italian owners) are cars that won’t be made in the U.S., and it’s fair to say those jobs are outsourced.

On the other hand, it’s high hypocrisy for Romney the free-trader private-equity guy to attack anyone for outsourcing production...

Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post dodged the fact that what the ad said was true by declaring that "The series of statements in the ad individually may be technically correct, but the overall message of the ad is clearly misleading." Kessler assigned his most damning designation of Four Pinnochios on this basis, yet he assigned zero to Obama's claim in his second debate with Romney about his communications regarding Benghazi which were only technically correct and technically was not even technically correct. The Columbia Journalism Review was founded by Victor Navasky, who has used his publication The Nation to, amongst other things, argue that Alger Hiss wasn't a spy for Stalin despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The CJR's Chittum nonetheless points out a mitigating factor re the Jeeps and China ad, namely that it started with a Bloomberg story with problematic wording and then was amplified inaccurately by a Washington Examiner blogger (before actually being dialed back in the Romney ad transcript from what the Examiner said). No such mitigating factor exists with respect to Obama's misleading claim in the second debate. Instead of getting "caught up in the liberal echo chamber," Obama's decision to create the impression that he called Benghazi a terrorist attack from Day 1 was a decision to create something, not picking up to forward on a liberal attack line already in circulation. Politfact, of course, also took a pass when it came to rating Obama's remarks, instead seeing the back and forth with Romney at the second debate as an opportunity to mark down Romney, calling his criticism of Obama on the point "half true." The bottom line here is that it's a mug's game to try and expose "fact checking" bias by pleading the "facts." One has to make an appeal to coherency, not correspondence.

There are other examples one could go into. Romney's infamous "47%... pay no income tax" remark was taken to task by fact checkers in part because "nearly two-thirds of households that paid no income tax did pay payroll taxes." Yet when it comes to trimming the growth of Social Security benefits, were these benefits paid for by tax revenue? In that case, the payroll taxes are spun as being insurance policy payments or otherwise "earned" benefits; in other words, when the question is whether the 47% are carrying their share of the load, their payroll taxes are deemed to be building up the public pot, but when the question is limiting S.S. payouts, these same contributions are deemed to be building up a private entitlement.

Now the example I meant to talk about today (but which I've taken a while getting to) goes back to my last post about the extent to which U.S. unemployment is cyclical or structural. In the context of the "fiscal cliff" debate the New York Times today claims that "Obama already agreed to more than $1.5 trillion in cuts last year." This $1.5 trillion number comes courtesy of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, however it should be noted that these "cuts" nonetheless still not only allow "discretionary" programs to continue to grow with inflation, they allow for a further $65 billion in spending above and beyond that over the next decade. How do you spin spending that exceeds inflation (and more) as "cuts"? By reaching back to inflated 2010 appropriation levels and using that as the baseline. The 2010 appropriation bills were actually adopted in 2009 when the demand on the social safety net was near its height and when Democrats enjoyed a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate in addition to their majority in the House, except for some special bills in 2010 for disaster assistance, border security, and the Patent and Trademark Office which the CBPP of course also included in order to further inflate its baseline. The CBPP says that the 2010 appropriation "simply reflects the level that Congress deemed appropriate" at the time. Well of course. You could say the same thing about 2007, or 2013 (we're already more than than two months into the 2013 fiscal year), but of course then the claim of $1.5 trillion in "cuts" would collapse.

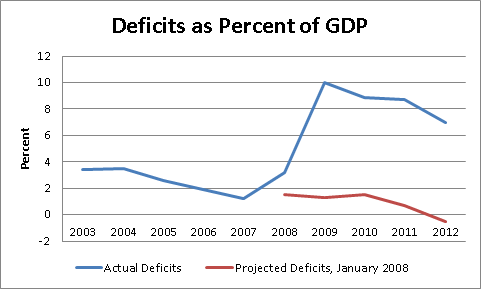

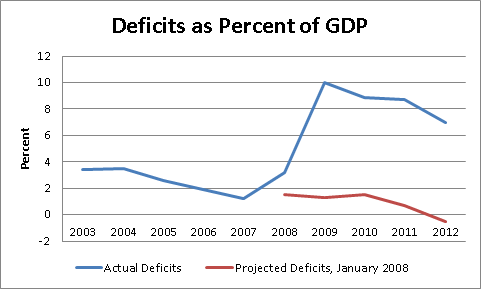

Now what would be an appropriate baseline? The answer to that is what is most coherent with the view you have taken elsewhere. Dean Baker, for example, has repeatedly insisted that the "graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy" is one that calls attention to projected deficits in January 2008 (I've copied his graph here). The blogger Kevin Drum insists on using a graph that he cuts off at 2008 in order to argue that "Washington Doesn't Have a Spending Problem." Drum says he cuts off his chart because "numbers in the chart have spiked over the past four years because the recession has temporarily depressed GDP and temporarily increased spending, but that spike will disappear naturally as the economy recovers". Yet Drum elsewhere tallies up "Discretionary spending cuts already passed in 2011: $1.5 trillion" No "natural disappearance" here, it's "cuts already passed" by Congress! Not passing another disaster relief bill like in 2010 becomes passing a cut. Coherency here would mean tallying up the change in spending since 2008, although that would of course completely undermine the point about all the "cuts" that have occurred.

Now what would be an appropriate baseline? The answer to that is what is most coherent with the view you have taken elsewhere. Dean Baker, for example, has repeatedly insisted that the "graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy" is one that calls attention to projected deficits in January 2008 (I've copied his graph here). The blogger Kevin Drum insists on using a graph that he cuts off at 2008 in order to argue that "Washington Doesn't Have a Spending Problem." Drum says he cuts off his chart because "numbers in the chart have spiked over the past four years because the recession has temporarily depressed GDP and temporarily increased spending, but that spike will disappear naturally as the economy recovers". Yet Drum elsewhere tallies up "Discretionary spending cuts already passed in 2011: $1.5 trillion" No "natural disappearance" here, it's "cuts already passed" by Congress! Not passing another disaster relief bill like in 2010 becomes passing a cut. Coherency here would mean tallying up the change in spending since 2008, although that would of course completely undermine the point about all the "cuts" that have occurred.

My last two blogposts about the U.S. prior to this one were about whether the current U.S. economic situation is the "new normal" and whether Obama's remarks at the second presidential debate were misleading or not. People can disagree with the former and say that 2007 should be the touchstone, but if so, don't elsewhere start calling a level of federal government spending that was decided in 2009 the appropriate reference point. People can disagree about my negative take on Obama's claim in October about what he said on September 12 by saying his words were narrowly true, but don't elsewhere say that Romney was a liar because while his ad was narrowly true it's what viewers were lead to believe that matters.

Now the example I meant to talk about today (but which I've taken a while getting to) goes back to my last post about the extent to which U.S. unemployment is cyclical or structural. In the context of the "fiscal cliff" debate the New York Times today claims that "Obama already agreed to more than $1.5 trillion in cuts last year." This $1.5 trillion number comes courtesy of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, however it should be noted that these "cuts" nonetheless still not only allow "discretionary" programs to continue to grow with inflation, they allow for a further $65 billion in spending above and beyond that over the next decade. How do you spin spending that exceeds inflation (and more) as "cuts"? By reaching back to inflated 2010 appropriation levels and using that as the baseline. The 2010 appropriation bills were actually adopted in 2009 when the demand on the social safety net was near its height and when Democrats enjoyed a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate in addition to their majority in the House, except for some special bills in 2010 for disaster assistance, border security, and the Patent and Trademark Office which the CBPP of course also included in order to further inflate its baseline. The CBPP says that the 2010 appropriation "simply reflects the level that Congress deemed appropriate" at the time. Well of course. You could say the same thing about 2007, or 2013 (we're already more than than two months into the 2013 fiscal year), but of course then the claim of $1.5 trillion in "cuts" would collapse.

Now what would be an appropriate baseline? The answer to that is what is most coherent with the view you have taken elsewhere. Dean Baker, for example, has repeatedly insisted that the "graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy" is one that calls attention to projected deficits in January 2008 (I've copied his graph here). The blogger Kevin Drum insists on using a graph that he cuts off at 2008 in order to argue that "Washington Doesn't Have a Spending Problem." Drum says he cuts off his chart because "numbers in the chart have spiked over the past four years because the recession has temporarily depressed GDP and temporarily increased spending, but that spike will disappear naturally as the economy recovers". Yet Drum elsewhere tallies up "Discretionary spending cuts already passed in 2011: $1.5 trillion" No "natural disappearance" here, it's "cuts already passed" by Congress! Not passing another disaster relief bill like in 2010 becomes passing a cut. Coherency here would mean tallying up the change in spending since 2008, although that would of course completely undermine the point about all the "cuts" that have occurred.

Now what would be an appropriate baseline? The answer to that is what is most coherent with the view you have taken elsewhere. Dean Baker, for example, has repeatedly insisted that the "graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy" is one that calls attention to projected deficits in January 2008 (I've copied his graph here). The blogger Kevin Drum insists on using a graph that he cuts off at 2008 in order to argue that "Washington Doesn't Have a Spending Problem." Drum says he cuts off his chart because "numbers in the chart have spiked over the past four years because the recession has temporarily depressed GDP and temporarily increased spending, but that spike will disappear naturally as the economy recovers". Yet Drum elsewhere tallies up "Discretionary spending cuts already passed in 2011: $1.5 trillion" No "natural disappearance" here, it's "cuts already passed" by Congress! Not passing another disaster relief bill like in 2010 becomes passing a cut. Coherency here would mean tallying up the change in spending since 2008, although that would of course completely undermine the point about all the "cuts" that have occurred. My last two blogposts about the U.S. prior to this one were about whether the current U.S. economic situation is the "new normal" and whether Obama's remarks at the second presidential debate were misleading or not. People can disagree with the former and say that 2007 should be the touchstone, but if so, don't elsewhere start calling a level of federal government spending that was decided in 2009 the appropriate reference point. People can disagree about my negative take on Obama's claim in October about what he said on September 12 by saying his words were narrowly true, but don't elsewhere say that Romney was a liar because while his ad was narrowly true it's what viewers were lead to believe that matters.